Things That Go Bump On The Net

A talk about how our folklore makes its way into how we think about technology, and how our technology itself spawns its own folklore. Written for and debuted at Electromagnetic Field 2018.

Cross-posted to Medium.

This is the longhand script that I ended up reading onstage, having not finished writing the thing in enough time to learn it. As a result, this is pretty much what I said verbatim - bar some adlibbing. In this written version you’re not getting some bits of ambient audio, a couple of slides and my impeccable comic timing. I have, however, added links off to original sources and whatnot.

Accompanying notes can be found here.

👻 👻 👻

First up, some housekeeping: thanks to EMF for having me again, and youse all for turning up.

I’ll start with a disclaimer: this talk is at something like version 0.8. There are probably bugs. By continuing to sit here you agree to be bound by the terms of my beta test agreement. If you think I’ve missed a trick, or a particularly good story, please come and find me later.

Also, it turns out that this is an ambitious topic to fit into half an hour. I’ll be glossing over a few things, passing by others at speed. I’ll assume that everyone’s clever people and has google to follow up things up later. I’ve published a lot of notes and references for this talk online.

With that said, let’s get started… 174 years ago.

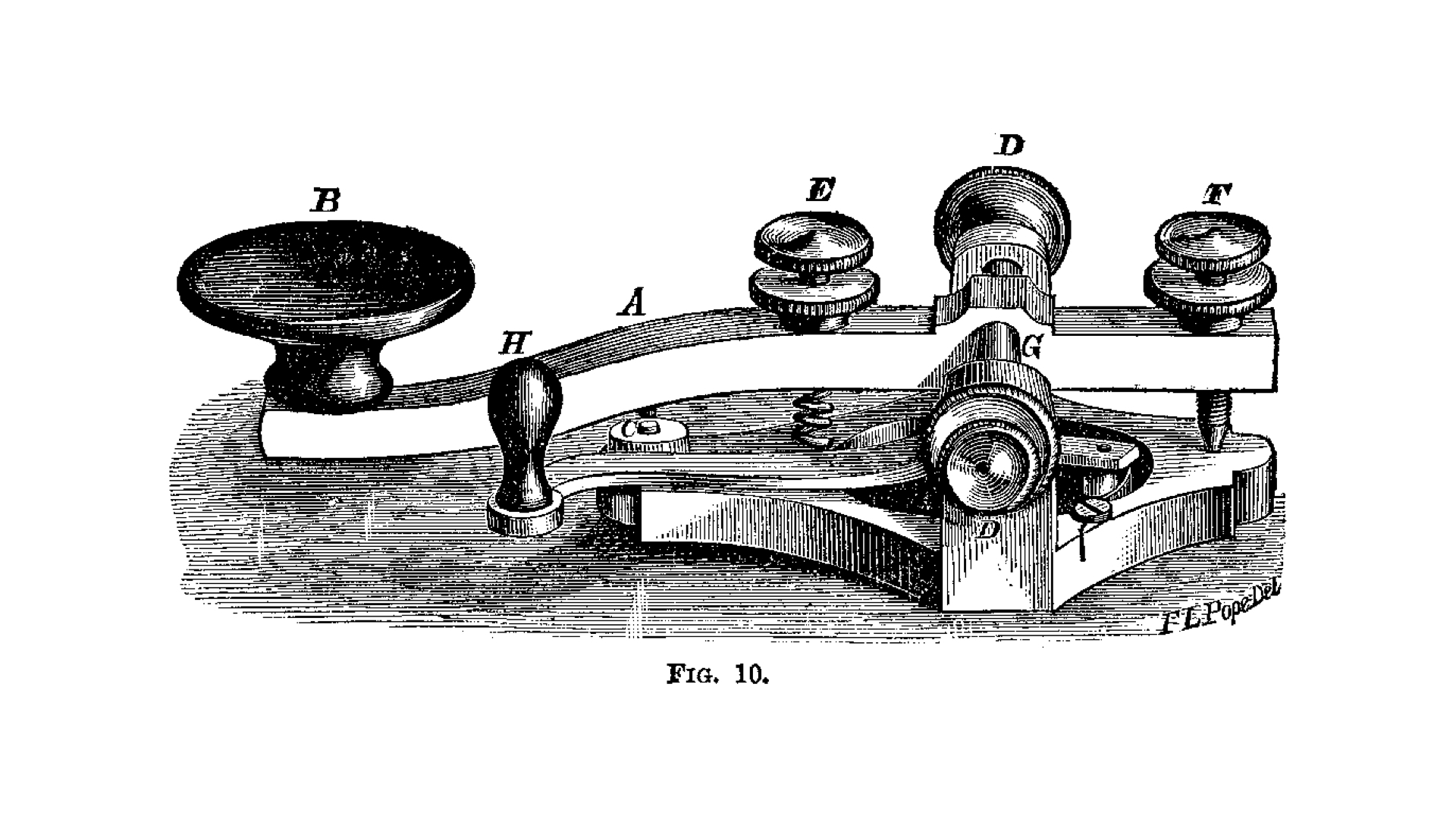

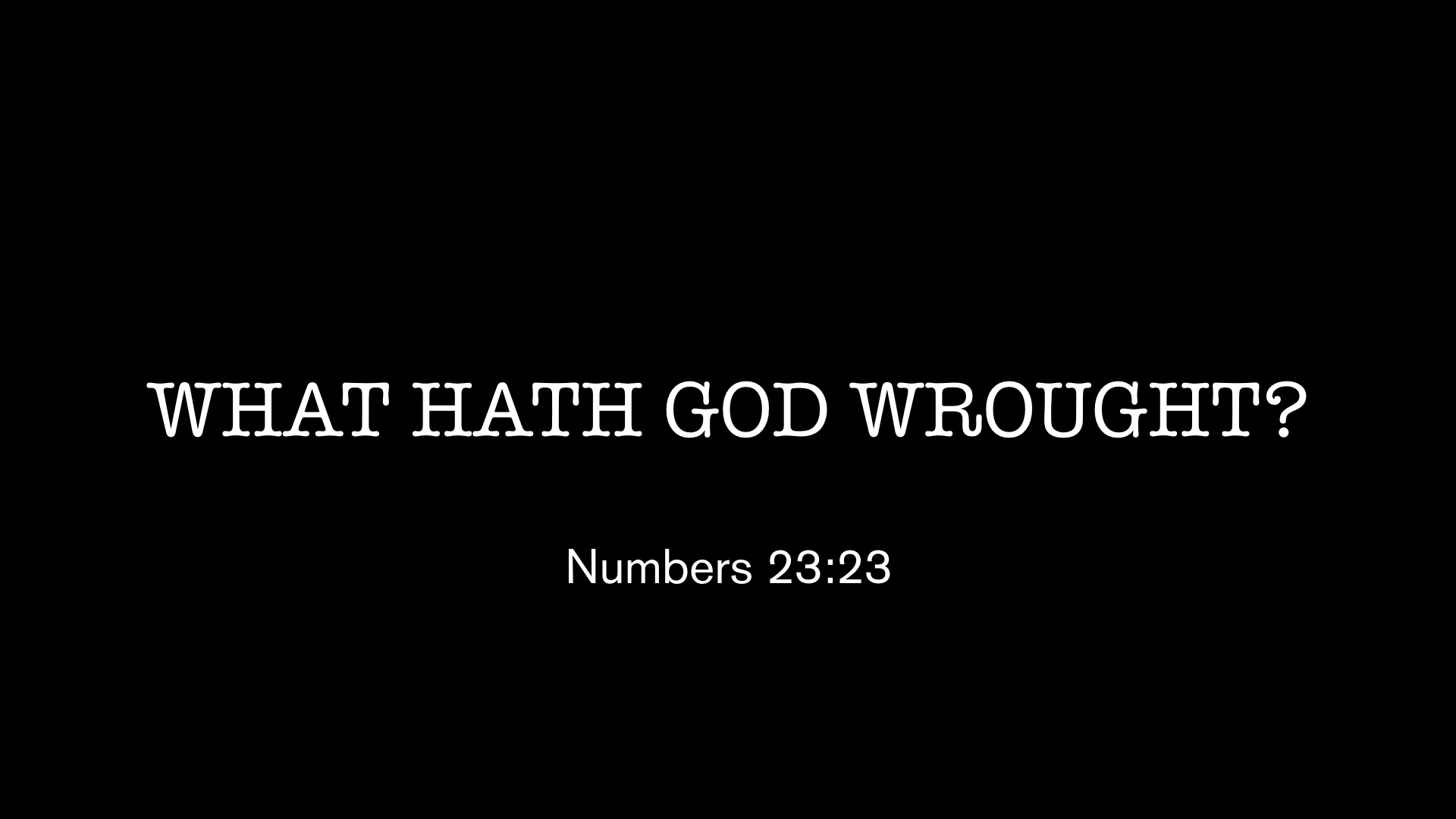

On May 24th, 1844, Samuel Morse sent the first long-distance telegraph message across America, from Washington D.C. to Baltimore.

He sent this quote from the Bible’s Book of Numbers. It’s a dramatic choice, for sure, and you can’t help but read as some kind of premonition (or at least monumental hubris) on Morse’s part, concerning the communications revolution he was helping to bring about. It’s also interesting though, because it frames the telegraph as a gift from a higher power. From God, to Morse, to the rest of us. Morse is merely channeling God’s will.

Four years after Morse’s transmission, in 1848 in New York State, two sisters reported hearing knocking, rapping and banging sounds at night that weren’t being made by anyone in the house. In time, the Fox sisters started to communicate with the entity making these sounds. On March 31st, Kate, the youngest, invited it to repeat the snappings of her fingers.

It did. She then asked it to knock out her age, and that of her sister Margaret, and of their older sister Leah who had moved away. It did this too: 12, 15, 17. Over the next few days, they devised a code which included ‘yes’, ‘no’, and letters of the alphabet. Then, the Fox family fled the house, to nearby Rochester. The tapping spirit followed.

Kate and Margaret became famous, demonstrating the first paid public seance in November 1849 and going on to successful careers as spirit mediums… until their confession in nearly forty years later 1888 that it was all a hoax. By that time though, it was far too late - Spiritualism had well and truly taken hold in the popular American - and British - imagination.

In his book ‘Haunted Media’, Jeffrey Sconce suggests that the story of the Fox sisters and that of Samuel Morse are far from unrelated. The telegraph, along with its fundamental mechanism for sending messages over long distances, had also brought with it a whole new set of ideas about communication with other bodies. Once you’ve abstracted communication out to something that can happen instantaneously, with no idea of who or what is on the other end of the line, then it’s easy to take that abstraction one step further and imagine communication with entities on other planes of existence, communicating through more ethereal means than a simple wire.

Now, at this point I really should mention radio and EVP - electronic voice phenomenon - but to be honest that’d be a whole half hour by itself. That’s definitely one to look up later though, if you’re interested and don’t already know about it.

83 years on from Kate & Margaret’s tapping spirit: 1931. Accounts of contact with strange creatures, or spirits, weren’t that uncommon. The Spiritualist movement, kickstarted by the accounts of the sisters Fox, had been running for around 45 years now, and people had been communing with voices from other planes of existence with some regularity.

In an isolated farmhouse on the Isle of Man, the Irving family - Jim, Maggie and their 12-year-old daughter Voirrey - reported hearing scratching and rustling noises coming from inside the hollow walls. These noises were apparently made by a trapped mongoose; one with yellow fur, and hands and feet, who had been born in New Delhi in 1852. They knew this because Gef spoke to them.

“I know who I am but I shan’t tell you. I am a freak. I have hands and I have feet, and if you saw me you’d faint, you’d be petrified, mummified, turned into stone or a pillar of salt.”

Of course, Gef couldn’t speak at first - he just squealed and thumped inside the walls of the house. However, in time, he started to make gurgling noises, like a child, and with encouragement from the isolated Irvings, he picked up English - not least through Jim’s daily readings to him from the newspaper. Gef could also speak the odd phrase of Russian, Spanish, Welsh, Hebrew, Manx and Hindustani - he was a well-travelled mongoose. As he himself is reported to have said:

“I was brought to England from Egypt by a man named Holland. When I was in India, I lived with a tall man who wore a green turban on his head. Then I lived with a deformed man, a hunchback.”

As Gef’s confidence grew, he started to explore the island, and brought gossip back to the farmhouse he’d heard while catching rides under the buses. He gained a nest under the rafters in Voirrey’s room, which the family called ‘Gef’s Sanctum’ and left bacon and sausages for him there, which he’d swipe while they weren’t looking.

With his confidence grew his notoriety. Gef’s story spread around the island, and in 1932 was reported on by The Isle of Man Examiner and The Isle of Man Weekly Times. From there, it was picked up by the mainland press, and before long the Irving’s farmhouse was getting frequent visits from journalists and paranormal investigators.

Gef never appeared to any of them, though - although he would rattle and scream while they were there. He saved particular ire for one Harry Price and his dictaphone:

“Is it that spook man Harry Price? Why, I won’t speak into it. I’ll go and smash his windows. I’ll drop a brick on him as he lies in bed.”

Of course, the most likely explanation was that Gef was, as Sconce puts it, “an imaginary companion, created by […] Voirrey. […] A creative girl’s reaction to prolonged isolation and boredom.”

The story of Gef adds another layer, though: if we accept that it was indeed a hoax, then it was one enabled and accelerated by the communications technologies of the day. Voirrey’s imagination was fed by the information that made it to the farmhouse at Cashen’s Gap through books, newspapers, radio - this was one of the things that made Gef more interesting than a ‘usual’ haunting, where the voices tend to bang on about the the ethereal mysteries on the other side of the vale.

“I’ll split the atom! I am the fifth dimension! I am the eighth wonder of the world!”

The story itself spread on the same networks that fed it. The tabloid press, knowing a good story when they saw one, gave extensive coverage to Gef, and by 1935 he’d made it as far as the Hong Kong Telegraph. The story’s so potent that it’s continued to propagate down through time to the present day, jumping from newspapers to books to magazines and the internet - even a field in Gloucestershire in 2018.

At the last EMF Camp, I talked about numbers stations - mysterious, shortwave radio stations that operated across Europe during the Cold War, mostly broadcasting strings of numbers. Most people think these were coded communication channels, broadcast by state intelligence agencies - although none have ever ’fessed up to running them, officially. During that talk, I said that the thing I found interesting about the numbers stations was the way that they acted as a kind of generator of folk tales, and that I reckoned you could draw a line back from the stories the numbers stations spawned to campfire ghost stories.

Today, I’m talking about my attempts to trace that line: how existing folklore makes its way into how we think about new technology how our technologies themselves generate their own folklore.

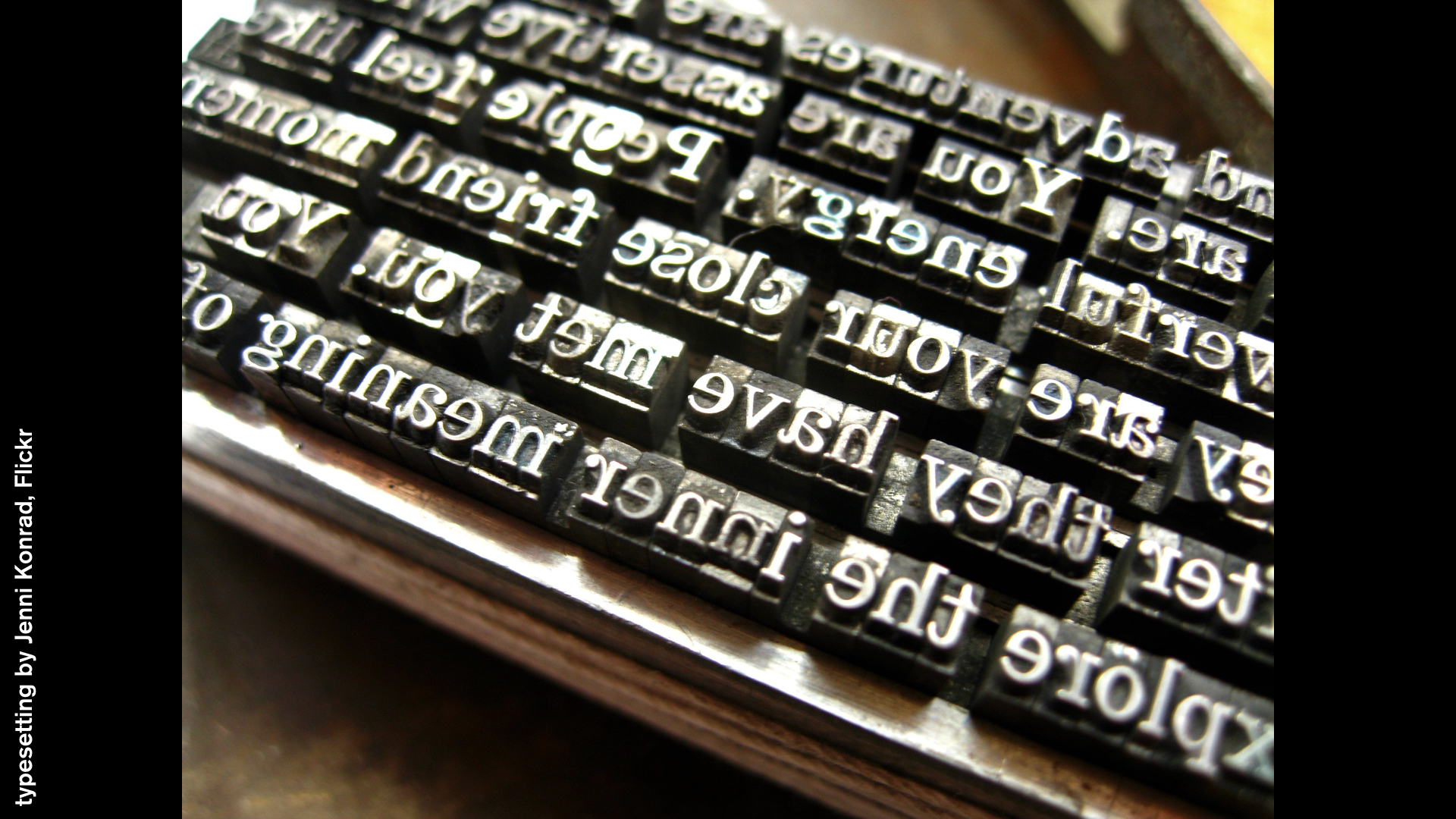

One of the earliest examples I could find of a technology spawning its own distinct folklore - as opposed to existing ideas about spirits manifesting in a new context - was Titivillus, the printer’s devil, who crept into print shops and introduced errors into carefully laid-out type overnight.

There’s also an idea in Japanese folklore of Tsukumogami - spirits which tools acquire when they get old enough. These spirits are harmless enough - mostly playing whimsical pranks on their owners - unless you annoy them by throwing them away too soon, or being wasteful.

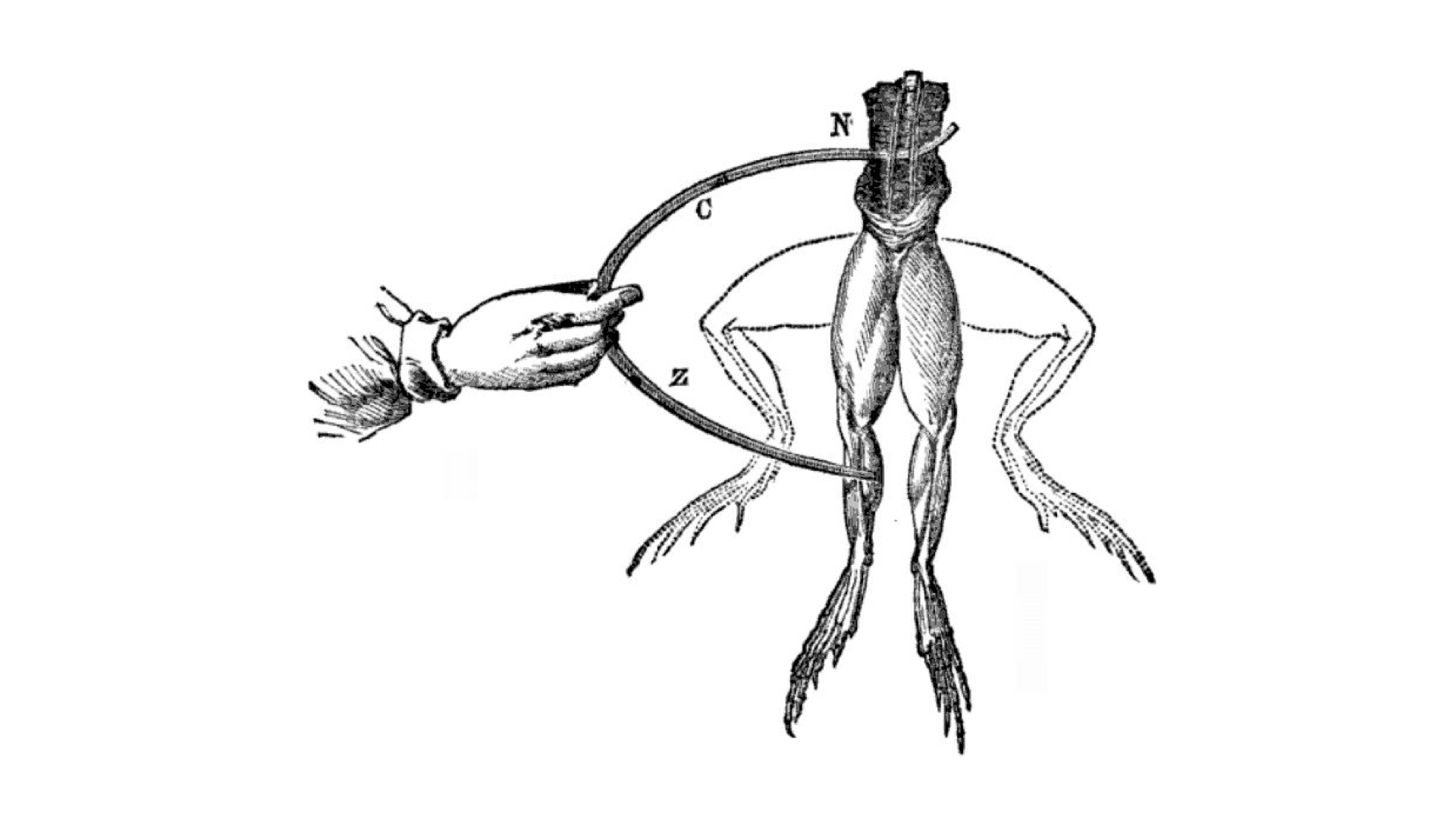

Galvani’s experiments, twitching frogs’ legs with electricity in the late 18th century give us Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and eventually the ‘killer AI’ myth, where an artificial child wreaks revenge on its creator.

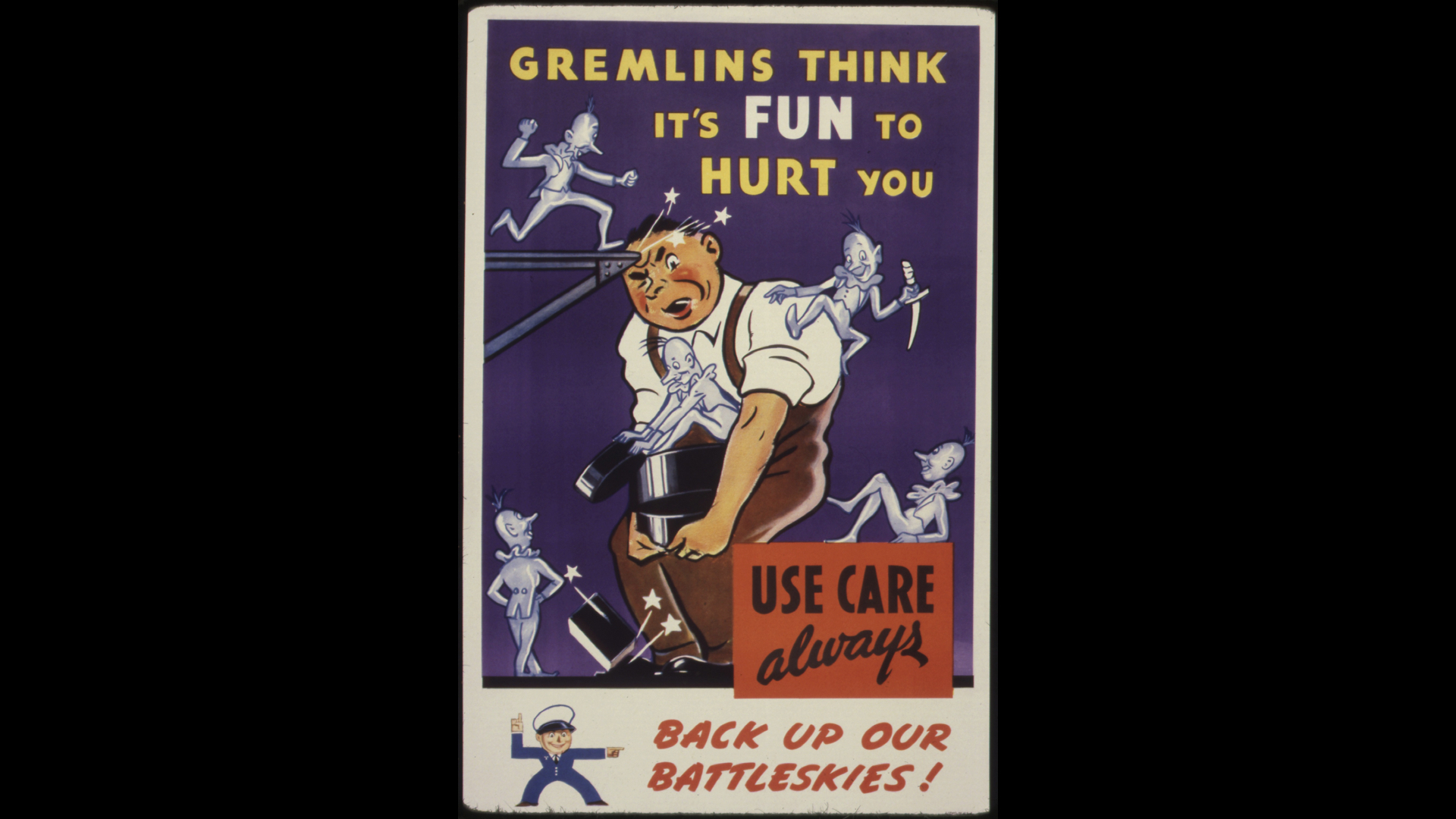

One of the first examples from the 20th century are Gremlins. These mischievous little imps were said to infest aeroplanes, and had an advanced knowledge of aeronautical engineering - which they used for devilry. It was common for pilots to blame mechanical problems with their aircraft on the gremlins - some even claimed that the gremlins could communicate with them on a psychic level, causing their vision to fog, or to see mountains which weren’t there.

Here’s an apparent account by ‘L.W’, a B17 ‘Flying Fortress’ pilot during World War II.

“So I am very aware of my surroundings, and as I go higher, I notice an unusual sound coming from the engine. The instruments went nuts. I look at my right and I see an entity staring at me. Then I look at the aircraft’s nose, and there it is another one, hanging in there. Dancing lizards.”

“But I was perfectly fine…my senses were in good shape, but the weird things were still there looking at me. They kept going at it, pounding the plane with all their might.”

“They appeared to be laughing, with their big mouths open, looking at me, hitting the plane with their long arms, trying to pull stuff. I have no doubt in my mind that they were trying to crash it. I managed to stabilize the flight and I saw the critters falling off the aircraft. I don’t know if they fell and died, or if they jumped from my plane to a different one. I have no idea.”

So again, let’s assume that the gremlins aren’t really real, and the product of some other, more explicable phenomena. And let’s put aside the observation that they’re pretty good examples of the trickster archetype - I’m sure we all know what that is, or can google it later.

Today, we’re interested in what could cause the myth of the gremlins to come about, and what purpose it served.

The most widely held theory is that oxygen can be in short supply in a high-altitude aeroplane, and lack of it could easily cause hallucinations. Other writers suggest that the gremlins served a morale-preserving function, allowing air crew to blame faults on something other than the maintenance crews, their comrades.

I think there might be something else going on here, too. A military plane is a fiendishly complex piece of engineering, with an awful lot of things that can fail in a lot of unpredictably interdependent ways. In other words: hard to understand. So once you hit a certain level of complexity, of unknowability - why not gremlins? Seems as plausible as anything else. It’s like the dark side of that ubiquitous Arthur C. Clarke quote that I won’t waste anyone’s time by repeating here.

And I think we can see this effect at work when we think about the stories that people make up to explain technology to themselves. Julie Carpenter, writing about mythmaking, says this:

The thing I liked about the numbers stations wasn’t just that they represented this tantalising, powerful mystery of the radio network; they also drew people together to try to work out what they were doing and why they were there. And when those stories intersected with the internet, the next generation of network, all kinds of weird things fly off as people take the idea and run with it. Photos appear, allegedly of site visits to defunct stations. Strange Youtube channels and Twitter bots appear, extending on the idea of hiding coded secrets in plain sight. The raw material of the story of the number stations - recordings, logs, theories of who might have been broadcasting them and why - get extended on by many imaginative minds.

Arthur Frank, writing about how stories work socially, says

and

It’s these social aspects of storytelling that I think gives us modern meme culture, the shared narrative sources and social functions of a story multiplied hugely by network effects.

A story like Slender Man, for example, who first pops up on the Something Awful forums in a Photoshop competition to make super-creepy images. His images show a faceless, gangly creature lurking in the woods behind some oblivious kids. However, the story swiftly takes on its own momentum as it comes into contact with many more creative minds, all adding their part to the legend, playing with fragments of folklore to create an ongoing, shared, viral narrative, popping up all over the internet in more creepy images and stories, implicating the Slender Man in atrocities large and small.

And at the same time as being a thoroughly networked fable, Slender Man simultaneously has its roots in our deep folklore. Shira Chess notes that:

“He owes many of his characteristics and some of his behaviours to fiction and folklore characters that preceded him”

She makes a connection between the Slender Man collective mythos and that of middle-European faerie lore, pointing out that many of Slender Man’s characteristics and behaviours - luring humans into traps, distorted or indeterminate body features, child abduction, a general air of unheimlich - all have precursors in traditional folk tales.

Slender Man turned out to be such a powerful story that it even infected old media. While writing this talk, I spotted these movie posters appearing along my commute:

Coincidence, I’m sure.

So we’ve seen that the way that we think and tell stories about our technologies actually has close ties to the ways that humans have always told stories about the world and interpreted phenomena. I want to spend the rest of this talk examining one particular strand of folk archetype: the oracular machine. And I’m going to start with the story of Roger Bacon, a 13th century friar and philosopher, and his alchemic bronze head.

According to the records, Friar Bacon wasn’t the first to cast a head from bronze in order to create an oracle - apparently, Pope Sylvester the 2nd made one in the 9th century (or stole it, with the aid of demons - but that’s another story). Several were said to have been built by Renaissance makers in the 12th and 13th centuries (interestingly though, most written accounts don’t appear until the sixteenth century). These heads were apparently able, after sufficient engineering or alchemic effort, to answer any question put to them, or make predictions about the future - but some, familiarly, could only answer ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

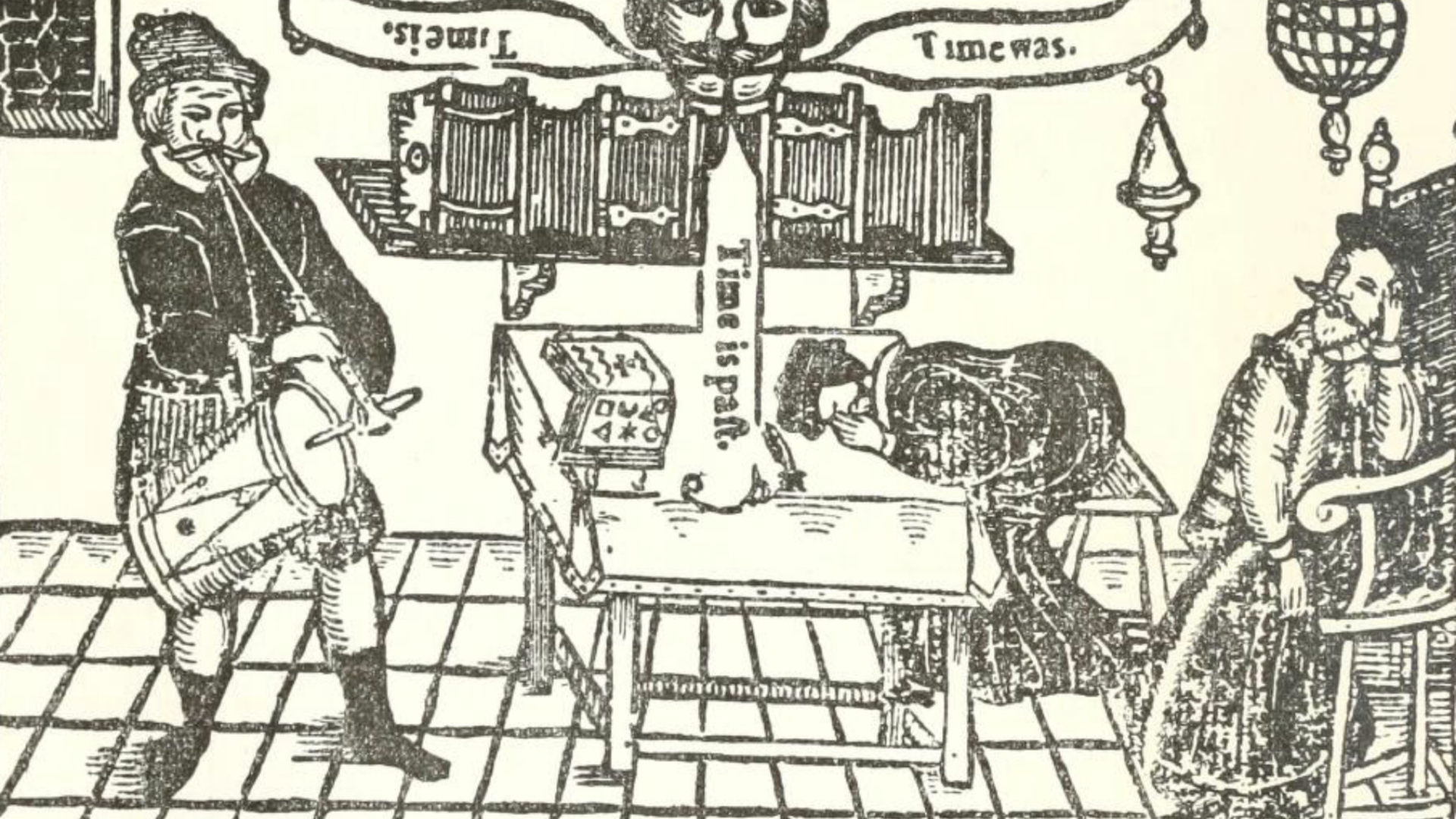

It’s the account of Friar Bacon which became the most famous though, thanks to the sixteenth-century playwright, Robert Greene. In Greene’s play, based, apparently, on a true story, Bacon and his assistant Miles spend a great deal of time and effort building a bronze head “that in the inward parts thereof there was all things like as in a naturall man’s head”.

Finally, they’re ready to animate it - which required keeping a continuous watch and also “the continuall fume of the six hottest simples” - plant extracts to you and me, your basic alchemic primitives. After three weeks of this, Bacon falls asleep, exhausted. While he sleeps, the head finally boots up and says three things:

Miles, still awake, freaks out so hard that he knocks the head over and it shatters. Bacon sleeps through the whole thing.

Years later, in 1837, Charles Babbage theorized that that given enough information, an entity might

“distinctly foresee and might absolutely predict for any, even the remotest period of time, the circumstances and future history of every particle”

He was thinking about a process which could model the whole universe, and thus predict the future.

Sound familiar?

The idea of a machine which can answer any question, has been with us for at least as long as we’ve been making machines - the original Mechanical Turk is in here, too. The idea that an engineer’s ingenuity can tell the future is also interlaced in with the Faustian myth of being granted great knowledge through esoteric means - but that knowledge usually comes with a price.

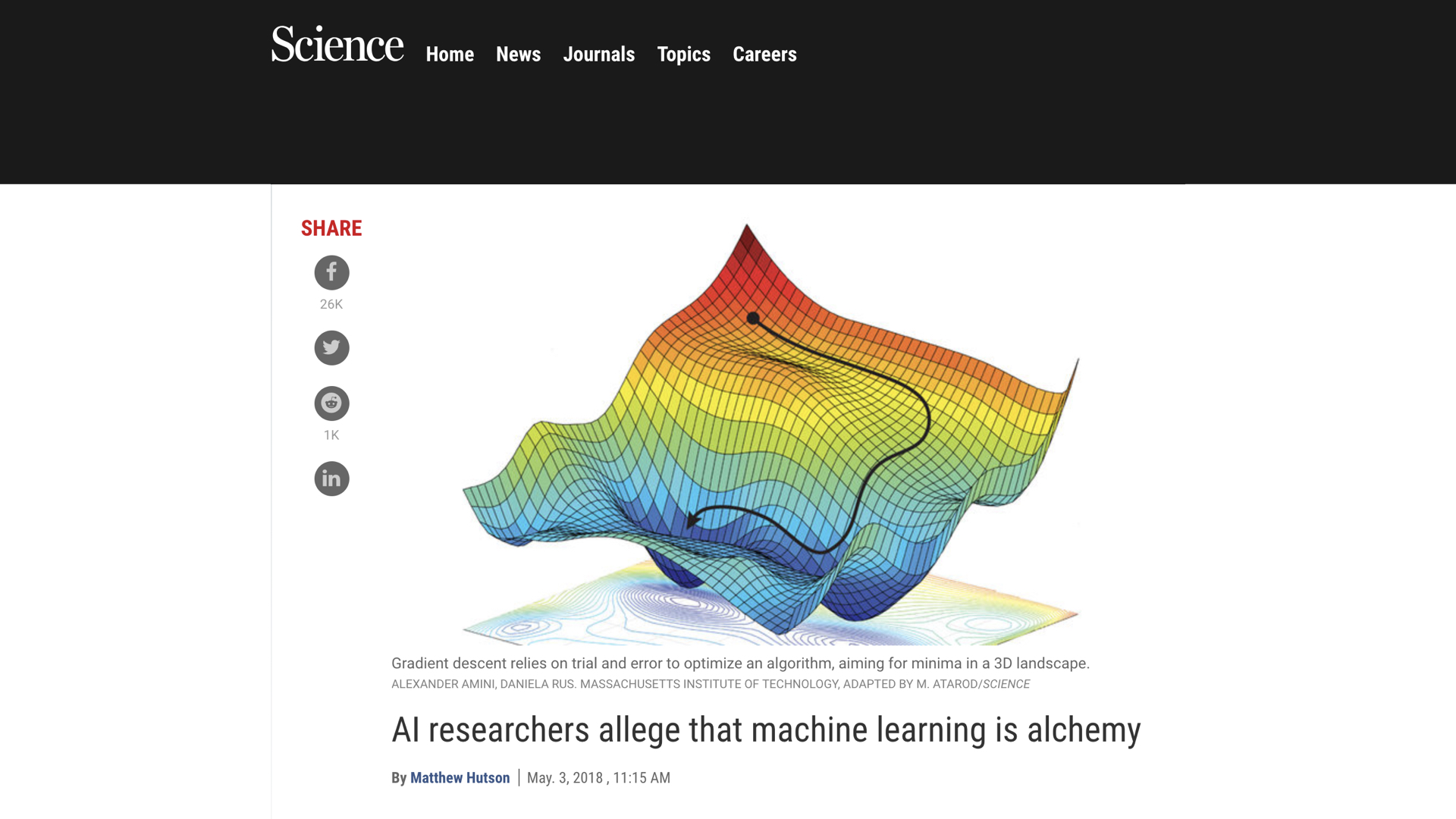

I think this archetype is alive and well in the ideas framing the discourse around Big Data & machine learning, and it’s not just me:

I think that alchemy is getting a bad rep here - it did, after all, lay the foundations for a lot of modern medicine and chemistry, after all. It did, though, also have its fair share of rituals that were enacted because the rituals themselves were thought to be powerful - and this is the analogy that Google’s researchers are making. They claim that most people doing ‘AI’ are following rituals that they’ve learned without really understanding the underlying science. Input datasets and training parameters are tweaked according to recipes people find on the internet, or learn and accumulate by trial and error. I suppose you could call that folk knowledge.

We have another problem in ‘AI’: it’s almost impossible to understand what’s happening inside a neural net. Sure, we understand how to set up the conditions that allow the network to build itself, and tweak those conditions to get the outputs we want, but we don’t even know why neural nets are so effective, let alone what’s going on in there. We’re creating black boxes.

But as long as we keep doing the rituals, the systems will behave.

It never ceases to amaze me that as an industry we’re actively involved in a project of hiving off more and more important data processing tasks to machine learning systems. Self driving cars, sure, but also setting insurance premiums, making healthcare decisions. Setting bail. Predicting someone’s chances of re-offending. Running the stock market. And at the heart of all these systems? Faith. Faith in unknowable black boxes.

He goes on to say:

“There are dangers in treating technology like magic. Scientists and engineers become priests and wizards whose pronouncements cannot be understood by the public, and implicitly, should not be challenged”

So I could end here, on a pithy summary that appears to neatly wrap everything up in a bow. But that seems like cheating.

We like neat resolutions - happy endings, elegant reversals, thematic resonance. We like frameworks, and that leaves us susceptible to a kind of narrative exploit. If a story seems to fit a pattern we know, we’ll accept it more easily because we know that story. Superstar CEOs are a neat fit for the hero’s journey. A new shiny thing is a fairy gift, powerful and capricious. All-knowing ‘AI’ systems become minor deities, capable of doling out judgement on us imperfect mortals. Deployment of these archetypes dulls our critical faculties, makes us more prone to magical thinking, absolves us of responsibility as we get swept up in the narrative.

And just as we like our stories to follow orders and structures, we like to think that our technologies are the product of science - rigorous, rational thought. But they are also the product of people - people like you and me, sitting down at a keyboard or a drawing board, bashing out their opuses. And those people are all embedded in a culture, grew up on particular stories. We can’t help but have the way we think shaped by those stories - in a way, those stories are what taught us to think. And we repeat those patterns.

So, I’m not going to end this neatly. But, if I am going to leave you with one thought, it’s this: keep alert. Reserve special scepticism for the stories which seem too neat, too powerful, too universally true, because they might just be regurgitation of our shared folklore to the bamboozlement of all involved.

Thank you.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the following friends, comrades and fellow-travellers who helped shape this talk in one way or another. All mistakes, however, are most certainly my own.

- Bill Thompson, whose fault it mostly is that I finished this talk.

- Garrett D. Tiedemann, who also shares a lot of the blame.

- Tom Armitage

- Natalie Kane

- Honor Harger

- Barbara Zambrini

- Alyson Fielding

- David Paliwoda

- Kim Plowright

- Ben Bashford

- Lydia Nicholas

- John V. Willshire